Imagine traveling on horseback through the gently rolling hills and open plains of Apulia with its olive groves, stands of pines and holm oak, and almond trees. It’s hot, the air leaves you feeling dry and parched, and your eyes hurt from the strain of the bright sun. Then, adjusting your hat, you happen to glance up, and you forget all about your discomfort. In the distance, on top of a hill surrounded by dark green pine trees like a giant royal mantle spread out around a throne, a building dominates the landscape, glowing white and pristine against the clear blue sky, austere in its clean outlines, and unlike anything you have ever seen before.

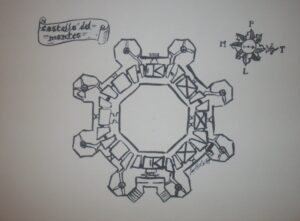

Castel del Monte from above [mons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=36033348]

Castel del Monte—literally ‘castle on a hill’—perches on a rocky plateau close to the monastery of Santa Maria del Monte at an altitude of 540 meters above sea level in the province of Barletta-Andria-Trani, in Apulia. In 1237, Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen commissioned the start of its construction. Sadly, it was not completed by the time he died in 1250.

Frederick II of Hohenstaufen (1194 – 1250), Holy Roman Emperor, King of Sicily, King of Germany, King of Italy, and King of Jerusalem, was arguably one of the most fascinating figures of his time.

Any historical portrait of Frederick II is bound to be filled with contradictions. Aside from his role as the emperor of a realm with enormous conflicts and social, cultural, religious, and political challenges, his interests were voracious and wide ranging, including law, falconry, and medicine.

Frederick II displayed skepticism, even disdain, with regard to religion and certain superstitious practices of his time. At the same time, he was also known for his fascination with mysticism and the occult. He could be ruthless and downright cruel in his pursuit of knowledge, conducting horrible experiments on children among others. On the other side of the ledger, he formally outlawed trial by ordeal. The emperor fostered a diverse and multi-faceted intellectual life at his court, embracing cultures from the East to the West and encouraging the natural sciences as well as philosophy, poetry, and mathematics. Frederick II spoke at least six languages, and he sponsored translations of scholarly works from Arabic, Greek, and Hebrew. He was one of the founders of the Sicilian School of Poetry and wrote beautiful poems and songs.

One of Frederick II’s passions was architecture, and his legacy includes an astounding array of castles, palaces, and cathedrals, the majority of which are located in southern Italy. According to some scholars, the emperor took an active hand in the planning, design, and construction of his various castles, including Castel del Monte, and they believe that he personally prepared drawings and plans for it.

Originally, scholars believed Castel del Monte was supposed to be a part of his network of strategically placed defensive castles and residences. Certainly, the terraces on top of the towers provide a panoramic view of the region, a strategic advantage in that enemies approaching from miles away would be visible to a lookout.

However, Castel del Monte lacks all the elements of a defensive castle such as a moat, a drawbridge, or a basement. There are no arrow slits and no trapdoors for pouring boiling oil on invaders. Nor are there any nearby towns or strategic crossroads that would explain the presence of a defensive structure. Its large marble-covered rooms indicate that it may have been intended as a lavish royal residence. Yet it also was more than a residence, equipped with 25 meter high limestone walls and 26 meter high towers.

Like other castles constructed at the behest of Frederick II, Castel del Monte exhibits elements from various architectural styles such as Roman, Norman, Arab, and Gothic. However, this remarkable structure is unique in its design.

The building is starkly modern and solidly medieval at the same time. The octagon structure is sometimes described as crown-shaped. With its eight octagonal towers framing an octagonal courtyard, it looks like a prism growing out of the ground when looked at from above.

When you are inside one of the towers and gaze up at the blue sky, it is as if the sky had transformed into an octagonal mosaic tile, set inside the white stones of the building.

The octagon of the footprint of the building is echoed in the shape of the towers and the arrangement of eight rooms, equipped with fireplaces, on each of the two floors. Winding staircases in three of the towers link these floors. A further fascinating architectural detail is the trapezoid shape of the rooms. Meanwhile, scholars argue that the octagonal floor plan was intended to represent the union of the square as the symbol of the earth and the circle as a symbol of the sky. This reflects Emperor Frederick II’s fascination with the language of symbolism, mysticism, and astrology.

Remarkably, the building was equipped with cisterns for the collection of rain water in five of the towers. Several towers also have baths with toilets and washbasins.

We don’t know whether Frederick II ever spent time in Castel del Monte. It wasn’t finished by the time he died on December 13, 1250 in his hunting lodge of Castel Fiorentino in the south of Italy. In truth, we don’t even know whether it was intended as a hunting lodge. Nevertheless, I couldn’t resist the temptation to create a scene in my book The Falconer’s Apprentice where my protagonist meets the emperor in the unfinished castle, sitting in one of the rooms at a table littered with architectural plans in front of a window with a view across the Apulian landscape.

After the emperor’s death, his son Manfred, the last King of Sicily from the Hohenstaufen dynasty, occasionally used it as a hunting lodge. King Manfred tried to carry on his father’s legacy, acting as regent on behalf of his nephew Conradin in 1254. Eventually, Manfred was overthrown by Charles of Anjou and killed in battle in 1266.

It is a bitter irony that King Manfred’s three sons—the last surviving grandsons of Emperor Frederick—spent a large part of their lives in the confines of the castle. After Manfred’s death, Charles took on the title of King of Sicily and imprisoned Manfred’s sons in Castel del Monte. The oldest was four at the time of his capture. Charles of Anjou kept the boys in heavy chains, in the dark, and with barely enough food to survive until 1299, when he transferred them to another castle.

Over the centuries, the castle was used as a prison, a refuge during a plague, and even as a secret navigational aid station, set up by the US 15th Army Air Force during World War II. Eventually it fell into disrepair. In the 18th century, it was repeatedly looted. Some of these looters were members of the House of Bourbon, who made off with marble columns and window frames. Originally, the rooms were decorated with precious polychrome marble, mosaics, paintings, and tapestries, but none of these remain. Only a few doors, still lined with colored marble, hint at the former splendor.

The Italian State purchased the castle in 1876. Meanwhile, it took another fifty years before the process of restoration finally began in 1928. In 1996, UNESCO awarded Castel del Monte the designation of a World Heritage Site.

[mons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=59358504]